On the afternoon of Sunday, September 14, 2025 at The Music Center’s Ahmanson Theatre, I enjoyed a dynamic performance of “I AM” by Camille A. Brown & Dancers. The show fused genres and questioned the typical audience-performer dynamic in a formal space. According to Brown, “I AM” was an exploration of Black joy, and the performers’ playfulness and energy brought this to life alongside impressive live music and upbeat, intricate choreography.

Before diving into the dancing, the musical composition and performance is worth mentioning. The score mixed original compositions with R&B hits from artists such as Busta Rhymes, The Temptations, and Mary J. Blige. The music was performed live by Kareem Matcham, Juliette Jones, and Martine Mauro-Wade, utilizing keyboard, violin, and percussion. The choice for more classical instrumentation offered interesting contrast with the musical influences and recognizable riffs. Their incredible performance could have been a standalone concert.

The program listed twelve section titles for the piece but the work mostly flowed together; a few of the section titles were projected behind the dancers but not all. The simple yet effective lighting and scene design was done by David L. Arsenault, and it used fog alongside the lighting for a recurring effect where dancers would seem to appear out of darkness in the back of the stage. In some of the group sections, lines of dancers doing different choreography would emerge for an effect that felt like there were vast numbers of dancers being slowly revealed to us.

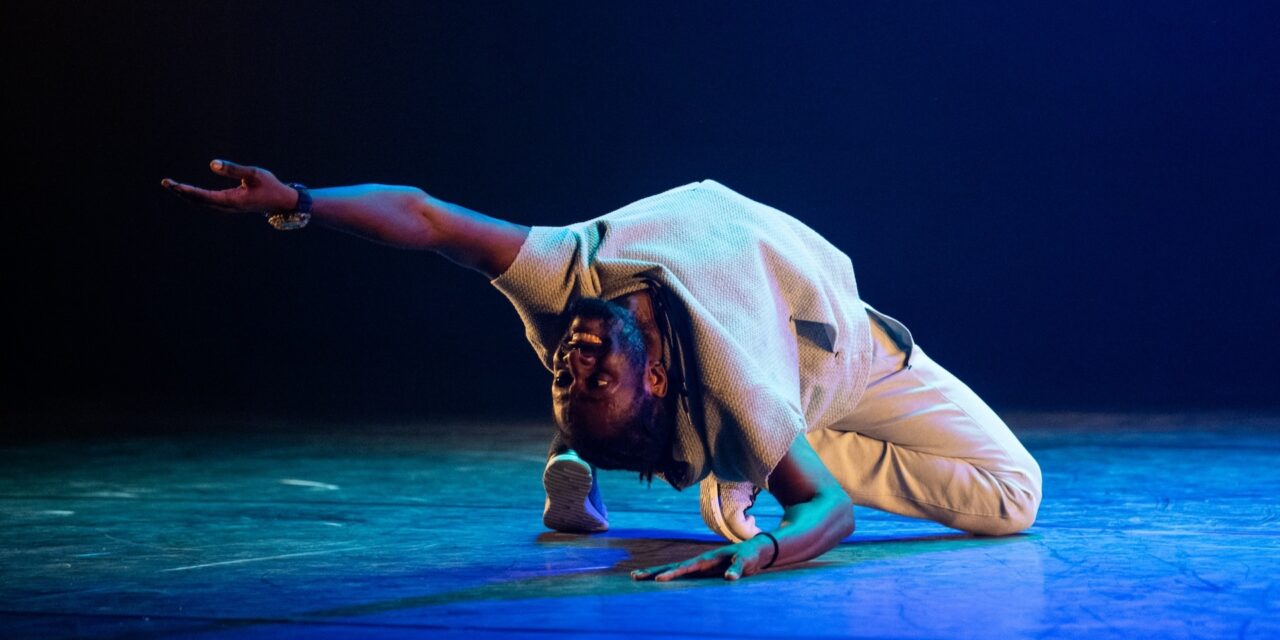

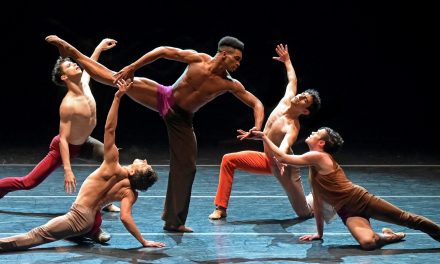

The cast consisted of thirteen dancers who worked well together and brought their own strengths to the production. They were dressed differently but mostly in white, which popped against the mysterious dark void created by the lighting and fog. Some dancers seemed to mostly exist as pairs, while others were more featured as individuals. The overall work was a fusion of vast styles, but in some sections, dancers would lean more into a style that they specialized in, like breaking, vogue, or step.

The piece as a whole began with the introduction of all the dancers. The footwork was often repeating bassline to the movement, and the upper bodies would undulate or employ sharp gestural work. The intricate polyrhythms highlighted layers of the music. I especially enjoyed when groups of dancers would execute different choreography to create exciting layering effects. However, at times in this section, particularly with a larger group, it felt like individual movement quality was compromised for the sake of togetherness. It seemed to me like they could have let loose a bit more while still being tied together by the pulse of the music.

In many of the solo sections, dancers were able to go all out into their individual styles – a highlight for me was a breakdance influenced solo that played with gravity and weightlessness. Especially in some of the slower moving sections, I enjoyed how the creases of the white fabric would accentuate the dancers’ undulations, making these subtleties visible in a large venue.

Another strong section commenced with a man gesturing in silence, playing with humor as he engaged the audience. Others enter and the group encouraged the audience to join in clapping. Underneath the loud clapping of the audience, the drum came in to begin the instrumental track. This section was heavily step influenced, featuring vocalizing alongside the body percussion, and the choice to stick with a single gender all-male group felt like a specific reference to HBCU Divine 9 stepping culture. While many of the pieces were more audience-facing, I enjoyed the interactions here as one dancer would stomp sharply in the middle while the group would circle more fluidly around him.

A frequent theme was the relationship between the instrumentation and the performance. In some sections, solo violin or piano provided a more classical feel that was contrasted by rhythmic dancing. In another section, two women pulsed and gyrated to the music, but as the layers of the music dropped out, I felt like I could still hear them through the continuing movement of the dancers.

The finale section brought high energy as layers of dancers moved on and off stage. Often when there were more dancers on stage, they were spaced out in a way that emphasized the vastness of the space. In this end section, it was climactic when the full group clumped together and moved in unison. From here, individual dancers were highlighted. The other dancers formed a semi-circle, and it felt like they were including us as the audience in this cipher-like tradition by letting us make up the other half of the circle.

Before the performance, the pre-show announcement featured an invitation to react and participate if it felt right. At times, the dancers seemed to intentionally engage with the audience to encourage that energy. The announcement and performance choices felt like an intentional choice by Brown to bring traditions of audience engagement that exist in step, in vogue, in breakdancing ciphers to a concert dance venue. Historically, Black art and Black joy have been excluded from these venues of so-called high art, and it felt like Brown was seeking to normalize this type of audience participation as a way of reclaiming the space in the image of Black styles rather than by assimilating.

In this exciting performance Brown showed strong aesthetic choices with the overall vision of the show from lighting to costuming. She also expertly fused together a broad range of styles, including more references that were beyond my level of understanding. At the end of the show, she appeared, dressed casually in a purple shirt that read Queens, from where she hails. She shared that the performance was dedicated to her recently passed father, and this was a beautiful tribute and celebration. Just the next day, it was announced that Brown will be choreographing the revival of “Dreamgirls” on Broadway, and this performance made me excited to try to catch this next step in Brown’s illustrious career.

The talented cast was made up by Dorse Brown, Mikhail Calliste, Nya Cymone Carter, Courtney Cook, Brianna Dawkins, Eboni Edwards, Kai Irby, Mykal Kilgore, Alain ‘Hurrikane’ Lauture, Jerimy Rivera, Courtney Ross, Curtis Thomas, and Travon Williams.

To learn more about Camille A. Brown & Dancers, please visit their website.

For more information about the Ahmanson Theatre, please visit their website.

Written by Rachel Turner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Camille A. Brown & Dancers – Photo by Cherylynn Tsushima Photography.