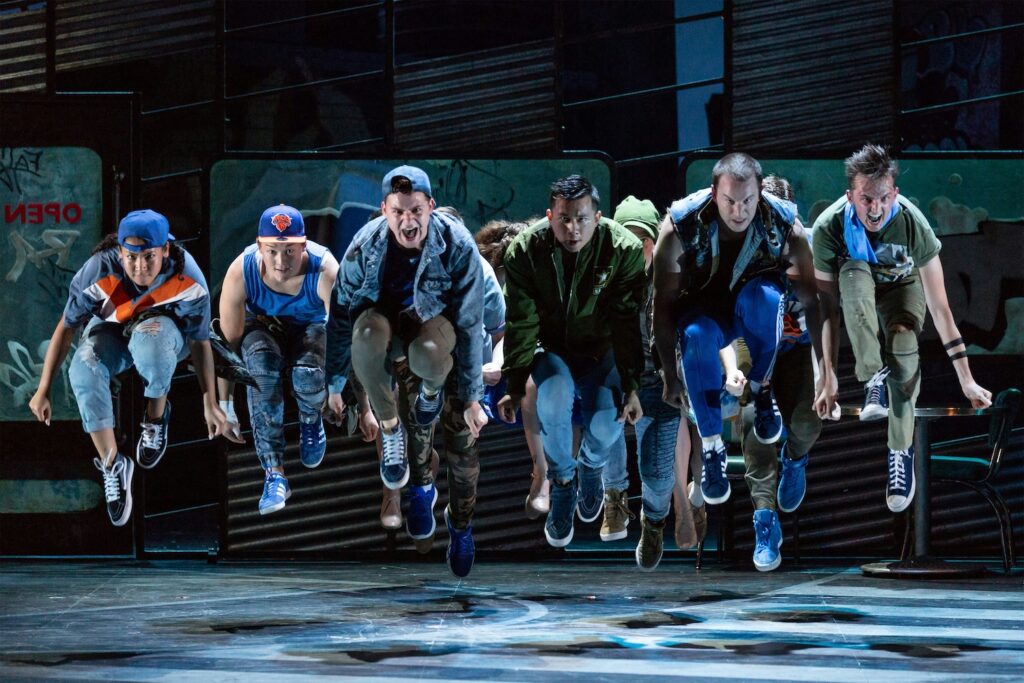

The combined Broadway magic of Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Jerome Robbins captured in West Side Story launches the LA Opera season with a production that sets a dance company worth of movers taking flight to an opera orchestra of a size that few theaters can match. Robbins’ drew on his New York City Ballet experience as well as his Broadway jazz chops creating dances closely knit into Bernstein’s melodies and Sondheim’s lyrics.

New for LA Opera, this production has been revived several times by the Lyric Opera of Chicago to high praise, most recently in 2023. Choreographer Joshua Bergasse is entrusted with reproducing Jerome Robbins’ original choreography, still as sharp as the finger snap that ignites this iconic retelling of Romeo and Juliet.

Considerable lore and legend surround the creation of West Side Story and its impact on Broadway in 1957, then the 1961 academy award-winning film version, and its ongoing presence in regional theaters, community theaters, high schools, and most recently, a film version directed by Stephen Spielberg with choreography by Justin Peck.

In addition to directing the original Broadway production, Robbins is credited with bringing the original concept to Bernstein after they successfully expanded Robbins’ ballet Fancy Free with music by Bernstein, into a successful Broadway musical On the Town. Robbins’ concept of an updated telling of Romeo & Juliet significantly evolved before Sondheim was brought in as lyricist and the concept became the musical that wowed Broadway in 1957.

West Side Story reportedly had more dance than any prior Broadway show, with Robbins gaining eight weeks of rehearsal, not the usual four. During the extended rehearsal weeks, Robbins developed the individual characters, reportedly giving each dancer a unique gesture repertoire specific to their character.

The story of Robbins’ choreography in the hands of Joshua Bergasse replicates that of musicians who trained with someone who trained directly with the composer.

During a break in the first onstage rehearsal, Bergasse spoke with dance writer Ann Haskins about his role reproducing choreography, how an iconic Broadway musical translates to an opera stage, and the efforts to achieve laser synchronicity between Bernstein’s notes and Robbins’ moves. (The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Haskins: The creative credits state “original choreography reproduced by” Joshua Bergasse. Why reproduce Robbins original choreography rather than new choreography?

Bergasse: What is so great about Robbins’ choreography for West Side Story, and why it works so well, is the parts of the show were designed together. The choreography was on an equal footing with Bernstein’s music and Sondheim’s lyrics. That’s why it is so affecting and so emotional when you watch it. When you take this specific choreography out and you add new choreography, it doesn’t work the same. I’m not going to judge whether it’s not good, but it is different and lacks a certain organic element. And that type of collaboration doesn’t happen very often now. With new musicals, you write the music, you write the script, and when you start staging it, you just add dance. West Side Story has Robbins’ choreography as an equal vocabulary in the storytelling.

Haskins: What does “original choreography reproduced” mean?

Bergasse: Basically, the major dance moments are all reconstructed from the original. My mentor was Alan Johnson. He was an understudy and then a replacement in the original Broadway production and learned the choreography from Jerome Robbins. He then became Jerome Robbins’ assistant and went on to set West Side Story productions for decades. I became his assistant in the mid-1990s and learned the replica production from him. Overall, this is not quite a replica production, but it is in the choreographic moments, with a couple of adjustments because the set is slightly different, things like that.

Haskins: Only a few people today can claim to have seen the 1950s original production. The 1961 film version is how most met West Side Story. Jerome Robbins started out choreographing that film, then things happened. He was fired but ended up with a co-director credit. How much of the 1961 film is the original Broadway choreography, and how much did he modify for the film?

Bergasse: Once he started the film, Robbins modified certain things for the camera. Angles may have changed for the camera, and ultimately, not every dance was in the movie, but as far as the choreography goes, the style of it and the steps, it is essentially the same. One of the other repetiteurs, who was Robbins’ assistant towards the end of Robbins’ life, said that if we really want to know what Robbins did in 1957, we should look at the 1961 movie. It’s the closest version, because Robbins started putting the movie together with a lot of the same people just a few years after Broadway. Whenever I have a question, like what is the intention? What did he really want? I look at the movie, for steps, for the intention.

Haskins: I understand Amanda Castro was Anita in the Chicago Lyric Theater production in 2023, but most of this cast is new. What were you looking for in casting the dancers?

Bergasse: We were looking for the dancers who have the technical ability to perform Robbin’s choreography. And we’re looking, in general, for whether they fit into the Shark gang or fit into the Jet gang. Also within each role, there are specific skills that are needed. Robbins gave each character gestures unique to that role. Can they play the role of the Jet’s leader Riff? Can they play the role of Action or another member of the Jets or the Sharks? Then we were looking at whether they could fit into what you were just seeing in rehearsal, the ballet section in Act II. The first part, the scherzo, has a lot of jumping. It is a very specific type of dancer that we need for that. And then in the pas de six, it is balletic and you have to be able to do the partnering. So it’s a lot of very specific things that we were looking for.

Haskins: I understand this is the first day of rehearsal on stage working out the choreography of the set and the dancing and the music.

Bergasse: It’s very exciting. We spend so much time in the rehearsal room. With this week getting into the theater and working with this set and matching the movement and music, is very exciting.

Haskins: Other than the two leads who are opera singers and the fact it is presented by the LA Opera or the Chicago Lyric Opera, what makes it an opera as opposed to a Broadway musical or does it cross over?

Bergasse: The show crosses over. It’s the Bernstein score. You don’t want to hear that with a six-piece band, you want to hear that with an opera orchestra. You want to hear these arias with the opera singers. And this particular set can’t play in regular regional theaters. This is a huge set; it’s really built for opera houses. In another theater they probably would have a smaller orchestra, they would have a smaller set, and they wouldn’t have opera singers.

Haskins: I’m curious about your thoughts on how Robbins choreography is embedded in Bernstein’s music, because it’s not simple music. Watching the dancers and the music go over certain sections multiple times, brought home how the knives being raised by Riff and Bernardo to start the fight is choreographed in both the dancing and the music. The knives hit their apex in the dancers’ hands and in the music at the same instant. Film scores match the action with technology, but Robbins and Bernstein wanted it to happen each show.

Bergasse: I think they shared the vision so closely, it was a true collaboration. It wasn’t just that Bernstein wrote a song, I think that they went back and forth a lot. There’s a story, and I don’t know if it’s true because it was 70 years ago, but the story is that Robbins just said, “there’s too many notes,” and he crossed out every third note in the score. Can you imagine doing that to Leonard Bernstein?

Haskins: What is the biggest challenge staging this choreography?

Bergasse: I think because I’ve done it so many times, and I’ve seen each individual part done so well, when I work with a new company, I want to raise everyone to that level. It’s not a frustration, but it’s a mission. When a cast member says, I can’t do that, that’s not possible. I’m like, I know it is possible because I’ve seen it done and it has been able to be done this way for 70 years. So I’m sure you can do it.”

Haskins: Two moments in the rehearsal were particularly striking. Just after the knives come out in the rumble, Riff and Bernardo both do a move, that resembles the squat Sumo wrestlers do to settle their weight before they make their first move. Was Robbins making an intentional reference?

Bergasse: Yes, I think that he was. And I tell them, don’t be casual about this. You think it’s a knife fight, but you are in choreography. Don’t, don’t be casual, you have started the dance.

Haskins: Another moment is in the pas de six where the dancers are in a line and starting with the center dancer offers their hand to the next dancer and that gesture extends along the line. It suggested a section with five dancers from Balanchine’s Serenade. Intentional?

Bergasse: Robbins was with City Ballet at the same time he was doing Broadway. So maybe. There is a lot to find. For example, the number “Cool” in West Side Story is very jazzy, like Opus Jazz that he did for City Ballet.

Haskins: I understand you also did On the Town about the three sailors which started as the Robbins ballet Fance Free for City Ballet and also has a Bernstein score. Were you working off of Robbins’ choreography for On the Town?

Bergasse: No, it was my own original choreography. There’s very little record of the original On the Town on Broadway, because that was 1944 and Robbins’ first musical. Fancy Free was one of his early ballets in April 1944, then they expanded it, turned it into On the Town, and in December 1944 it opened on Broadway, something that never happens now. I’m working on a show that we’ve been working on for 12 years now, Bull Durham, based on the baseball movie. It’s finally opening this year at the Papermill Theater in New Jersey.

Haskins: Is there anything else you want people to know?

Bergasse: I’ve been doing this for 30 years. It’s an honor to be a part of this history. It’s an honor to share it and work here at LA Opera. It’s really very special.

The 1957 original West Side Story was set in the 1950s. This production is present day, including a poster of Puerto Rican rocker Bad Bunny in Maria’s bedroom. The gangs are interracial, not strictly Hispanic and white. The tragic romance unspools into new decades, but Robbins choreography so interwoven with Bernstein’s music and Stephen Sondheim’ lyrics remains timeless. This show runs for only six performances.

West Side Story at the LA Opera, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave., downtown; Sat., Sept. 20, 6 pm, Sun., Sept. 21 & 28, 2 pm, Thurs., Sept. 25, 7:30 pm, Sat., Sept. 28 & Oct. 4, 7:30 pm, $32.50-$350. West Side Story

Written by Ann Haskins for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: LA Opera “West Side Story” – Photo by Todd Rosenberg.