Leaning into her third season as Artistic Director of San Francisco Ballet, Tamara Rojo is balancing the venerable heritage of America’s oldest ballet company with its equally venerable commitment to inventive creations that move the art form and its dancers forward. Rojo’s new initiatives include expanded international and national touring, including to SoCal. The San Francisco Ballet’s full-length “Frankenstein” arrives October 2-5, 2025 at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, and in July, the company joined the LA Phil at the Hollywood Bowl.

Trained in Spain, Rojo became a celebrated principal dancer and international star with the Scottish Ballet, English National Ballet, and Britain’s Royal Ballet, making guest appearances around the world, before returning to ENB in the dual role of Artistic Director and principal dancer. During a decade leading ENB, Rojo brought groundbreaking choreography into the repertoire, oversaw the construction of a new building, and was credited with breathing new life into ballet classics.

In January 2022, San Francisco Ballet announced Rojo would replace retiring artistic director Helgi Tomasson. Rojo inherited the 2023 spring repertory season, but curated the spring 2024 repertory, opening the season with a new ballet from choreographer Aszure Barton. That commission, “Mere Mortals”, considered Pandora’s Box as a metaphor for new technology, complete with rock music, and an after-party in the ornate lobby of the San Francisco Memorial Opera House. The balance of the 2024 season included full-length classics, ballets by British choreographers Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan, and works by women choreographers. The 2025 season also had an evening of contemporary English choreographers, one devoted to Hans van Manen, and full-length ballets including Rojo’s update of “Raymonda” and Liam Scarlett’s “Frankenstein”.

Dance writer Ann Haskins spoke with Rojo at San Francisco Ballet’s studios, where dancers returned in July to rehearse for “Nutcracker”, spring 2026 repertoire, and to prepare “Frankenstein” for Southern California. Rojo reflected on running a U.S. company after a career with English and European ballet, the direction her leadership has taken so far, and several telling moments that captured her vision, priorities, and style as Artistic Director for San Francisco Ballet.

Haskins: After the January 2022 announcement that you would be the next artistic director, there was an extended transition period. How did that work?

Rojo: It was approached as a collaborative process. After almost 40 years at the helm of an institution and considering the legacy he was leaving, it cannot have been easy to let go, but Helgi has been incredibly gracious and supportive. I am very thankful to him for that, and I am very aware of my responsibility to his legacy.

The transition allowed me a slow introduction to all the different parts of the organization. The artists, for example, the dancers, musicians, crew, and all the teams in marketing and development that needed to hear from me, what my vision was, what my plans were. Because it is quite a big Board of Directors, the selection process did not include the entire board who needed to hear from me, to meet me in person. I think I was first there in July for three weeks, and I came back in autumn, then I joined proper in December.

Of course, Helgi is still very involved. We have a lot of his repertoire. We do his “Nutcracker“ every year. We’re rehearsing his Don Q for next March, so he is in the studio and has final say of casting. It is still very much that kind of collaborative relationship, the ideal way of doing things, I think.

Haskins: Have been your priorities for San Francisco Ballet differed from your priorities at English National Ballet?

Rojo: I was very lucky at ENB, because I was able to really invest in the wellness of our dancers. One of the priorities at San Francisco Ballet was to strengthen our own wellness centre, bring in more experts to support the dancers, intimacy coordinators, fight coordinators, and also strength and conditioning experts.

Another aspect with the dancers is Creation House, programs to support dancers who want to start experiencing what happens after the dance career, opportunities for those interested in choreographing, and our own leadership program. It was also very important to me that we started developing and strengthening relationships of collaboration with the local dance and arts organizations, all the dance ecology and the arts ecology of San Francisco.

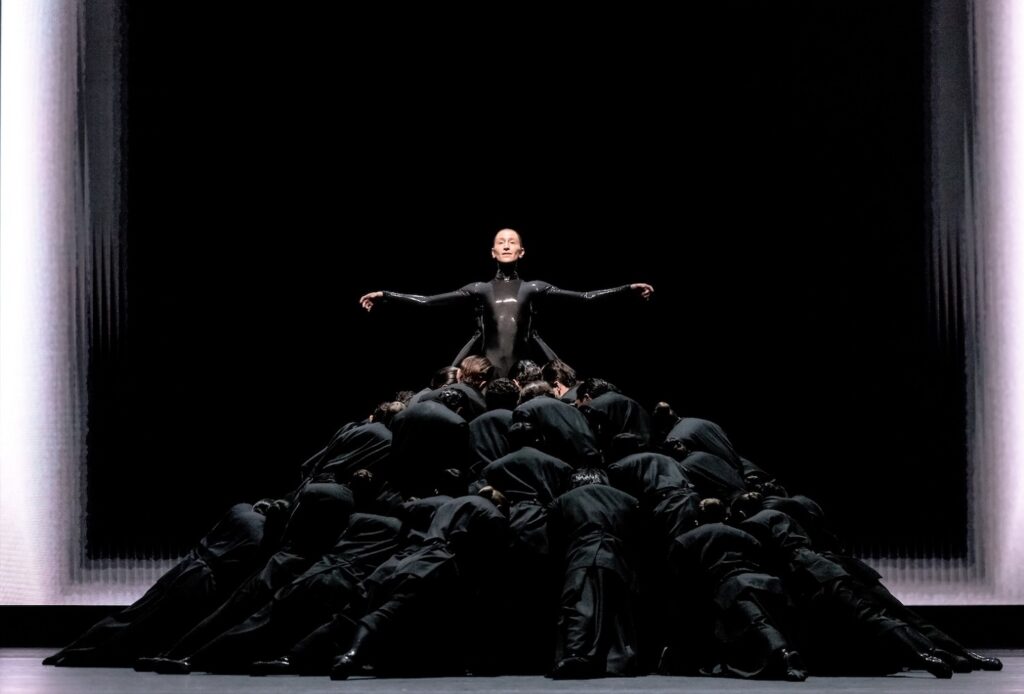

Jennifer Stahl and San Francisco Ballet in Aszure Barton and Sam Shepherd’s “Mere Mortals” – Photo by Chris Hardy.

At the same time, a priority was thinking about how to define San Francisco Ballet artistically, and I think that’s something that I believe I share with other artistic directors. It is important for a company to have their own characteristics, their own personality and their definition. What is San Francisco about? San Francisco is about innovation. San Francisco is certainly about new technologies right now and San Francisco Ballet has a long history of creating new works. So how do I add on into that legacy with something that is relevant now, that can reach out to our communities and make them feel that we are representative of the San Francisco and the Bay Area community? That’s why I commissioned “Mere Mortals”, which considers Pandora’s Box as a possible metaphor for new technology. Also, we brought the ballet about Frida Kahlo, who was in San Francisco with Diego Rivera. We want to bring in ballets relevant to all the cultures that exist here.

Another aspect of the things I wanted to do is re-establish a touring pattern and develop long, lasting relationships with venues. We’re taking Akram Khan’s “Dust” to New York for Fall for Dance in September, and in November, we’re back in New York with “Eugene Onegin” for the works in process at the Guggenheim. We were at the Hollywood Bowl in July, and we will take “Frankenstein” to Costa Mesa in October. We are looking at LA and expanding our presence there. We have a real path and a real plan about touring nationally and internationally.

Haskins: In 2024, the first repertory season curated by you, there was a week in February and a performance in April where your leadership substance and style seemed to click into gear. In February, an anonymous donor gave $60 million for new choreography – a gift considered a strong endorsement of your new leadership. Later that same week, you came onstage during final bows with an armful of flowers and announced the promotion of Jasmine Jimison to principal dancer. That is a common practice at many companies, but not at San Francisco Ballet. Was that something you thought about and decided to inaugurate?

Rojo: Yes, I thought about it. I want the audience to know our dancers. My role is to support dancers to reach their true potential, and part of that is the audience following their journey, sharing their success. We did it again when Cavan Conley became a principal dancer at the end of the season. Each time, we reached out secretly to their families to make sure they would be at the show.

Haskins: The second instance came in April 2024 at a highly anticipated, sold-out performance with guest artist Natalia Osipova dancing Swan Lake. Hours before the show, Osipova was injured in rehearsal, and a dancer scheduled to debut in the role over the weekend became the newbie replacing Osipova. Before the show, the audience clearly was agitated and understandably disappointed. You came onstage and what you said changed the situation. From the stage, could you feel the whole mood shift at what you were saying?

Rojo: May I share why I did that? At my very first show with the Royal Ballet, nobody knew me. I had never danced with them before. I came in to dance instead of Darcey Bussell and no one informed the audience until just before the curtain went up. There was a voiceover that just said, “In today’s show, the role of Giselle will be danced by Tamara Rojo instead of Darcy Bussell.” The audience booed.

I wanted to make sure that would not happen to my dancers. I wanted to make sure that if anybody was going to get booed, it was going to be me. That’s why I went in front of the audience, and I explained what had happened, what was going to occur, and what I thought was going to be an exceptional evening for all of us, because a star was about to rise to the highest possible goal in ballet, and she had the courage to do it. So I’m glad that I was able to do that for her because of my own experience.

Haskins: You have commented that your initial company experience in Spain was contemporary ballet with Victor Ullate, and you had to learn classical repertoire when you joined other companies.

Rojo: Our training with Victor Ullate was classical, and it was incredibly disciplined. We used to train a minimum of six hours a day from when we were 11 years old. It was very, very demanding training. He was a dancer with Béjart, and he was a creator. So the repertoire we were doing was not classical, so I didn’t know the classical ballet repertoire.

Spanish classical training has many important influences, a mixture of Russian, Bournonville and Cuban. What was useful for me, something at the time I thought was a negative, but now I realize it was a positive, was that I did not come from any school that had a pedigree. I didn’t come from the Bolshoi, the Mariinsky, the Paris Opera. I was really hungry to learn. I had no truth to defend, and I worked with many styles. My first “Giselle” was Cuban, but then I did the Royal Ballet version very quickly. After that, my first “Swan Lake” at the Scottish Ballet was Russian. Six months later, I was doing “Swan Lake” in London with the British version. Then I was invited all over the world and danced an array of productions. Very quickly I understood that everybody had their own version of what was classical, and everybody had their own version of what was correct. And therefore, as an artist, the best thing I could do is learn everything and then make choices that were appropriate for me, or for the audience, or for the context of the production, or for the vision of the choreographer. At the time, I felt very insecure about not having that pedigree, but that made me very hungry to learn. I was really a blank tablet. I was hungry to learn from all these people that told me that they had the truth and they had the legacy. Now, I realize that it gave me so much more knowledge than if I had just gone to one specific school.

Haskins: Was there a point where you began asserting your own truth?

Rojo: There was a time at the Royal Ballet, where I was persistently requested to dance in the manner of Margot Fonteyn. I was a very different dancer. I mean, physically, I had dark hair, and I was pale, and I was small, but I understood that we were different people with different physical attributes. It was then that I realized that I could no longer just do what I was told. There was a point in the maturity of an artist when there is a responsibility to do it differently. In fact, not doing it differently would be a disadvantage for the art form, because the art form moves forward by new creations, new compositions, but also by artists like Karsavina or Nijinsky or Pavlova or Sylvie Guillem, changing the way that we do things, changing the way we present ourselves on the stage. It was my responsibility as an artist to think for myself and, come what may, do what I felt was right on stage,

Haskins: Was that sort of the start of the “you” that said that I can run a company?

Rojo: It was partly frustration with the sense ballet in England had drifted away from the vision of Ninette de Valois, Alicia Markova, and other people, who had made ballet so instrumental in the psyche and the culture of the United Kingdom. Also, I was invited to meet with the then Prime Minister of Spain, and I was asked what it would take to really build a solid ballet company in Spain. I felt that if that opportunity ever was mine, I needed to be at least as good as the people I admire. That’s why I started to study more seriously to be ready to have my own company.

Haskins: Spain seems unable to sustain a ballet company.

Rojo: The problem with certain European countries is that their cultural institutions, their directors, and their budgets depend directly on a cultural minister, which tends to be a position given in return for something else, and the appointment of cultural directors is without any transparent process, without real thinking of the long term, and without building into the long-term future. If there is a change of government or a change of culture minister, the institutions’ leadership changes again, and the new leadership may shift support to a different dance than ballet. That happened with Victor Ullarte, with Ángel Corella, and that just happened to Joaquín De Luz, who was doing a very good job with the national ballet company [Compañía Nacional de Danza]. It happens over and over and over.

Haskins: American ballet companies look with some envy on the European model that provides government financial support to ballet companies, as opposed to this country, where ballet companies rely on ticket sales and private donors who also can be fickle. You’ve had to shift over to the American model. How’s that going?

Rojo: Well, I’m doing my best. I think there should be a happy medium. And I do believe that the happy medium is the British model for which we have to thank the economist John Maynard Keynes, who was married to the ballerina Lydia Lopokova. Mr. Maynard Keynes created the Arts Council in response to what had happened in Nazi Germany, where cultural institutions had been used to manipulate the masses. He wanted that to never happen again. He wanted an independent organization that received money from, but was not affiliated with, the government.

The Arts Council generally is composed of retired artists who decide what institutions should receive that funding, are looking at the arts institutions as their obligation, and looking at the long term, not looking to keep someone who appointed them happy. The Arts Council provides enough money for risk taking, but not so much public funding that artists don’t have a responsibility towards the audience. I think that mix is ideal.

I would love one day for governments here to understand that, like in Britain, for every dollar you invest in an arts institution, you’re going to receive five to $10 back in taxation because we are the supporters of the civic community. We support restaurants where the audience eats, hotels they stay at, transportation for the company and the audience, publishing of programs and marketing. It’s not just the artists that we are so happy that we can support, but all of the other industries that the arts really support. In fact, in Britain, at the time that I left, the creative industry was contributing about 120 billion a year to the UK economy, bigger than any other manufacturer. And so even if you don’t agree with the benefits of the arts themselves, if you want cities to be successful and places where people want to live, and want the general economy to be successful, you should want to invest in the performing arts.

Haskins: Is there anything else you would like to say?

Rojo: I just want to say thank you for coming. Sometimes in the West Coast we feel like unless the New York Times writes about us, we don’t exist.

Now that I’ve been here almost three years, I am of the opinion that everything that is creative is happening on the west coast – from Vancouver’s Ballet BC to Pacific Northwest Ballet; all the companies down in LA doing contemporary work; and here in San Francisco with ODC to Lines Ballet. We are really very creative, very much risk takers. We’re bringing the art of ballet forward.

Note: A longer version of this appeared in the European publication Gramliano.

Frankenstein – San Francisco Ballet with the Pacific Symphony at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, 600 Town Center Dr., Costa Mesa; Thurs.-Fri., Oct. 2-3, 7:30 pm, Sat., Oct. 4, 2 & 7:30 pm, Sun., Oct. 5, 1 pm, $59-$179. San Francisco Ballet – Frankenstein

For more information about the San Francisco Ballet, please visit their website.

Written by Ann Haskins for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Tamara Rojo – Photo courtesy of the artist.