On Friday, January 9, 2026 at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, I enjoyed attending one of two opening weekend performances as part of Dance at the Odyssey. This six week festival features two shows each weekend and 17 total choreographers and is worth checking out if this evening was any indication. The program I attended was a split bill: first Neaz Kohani’s “SHE IS MY SISTER,” followed by Owen Scarlett’s “GASP.”

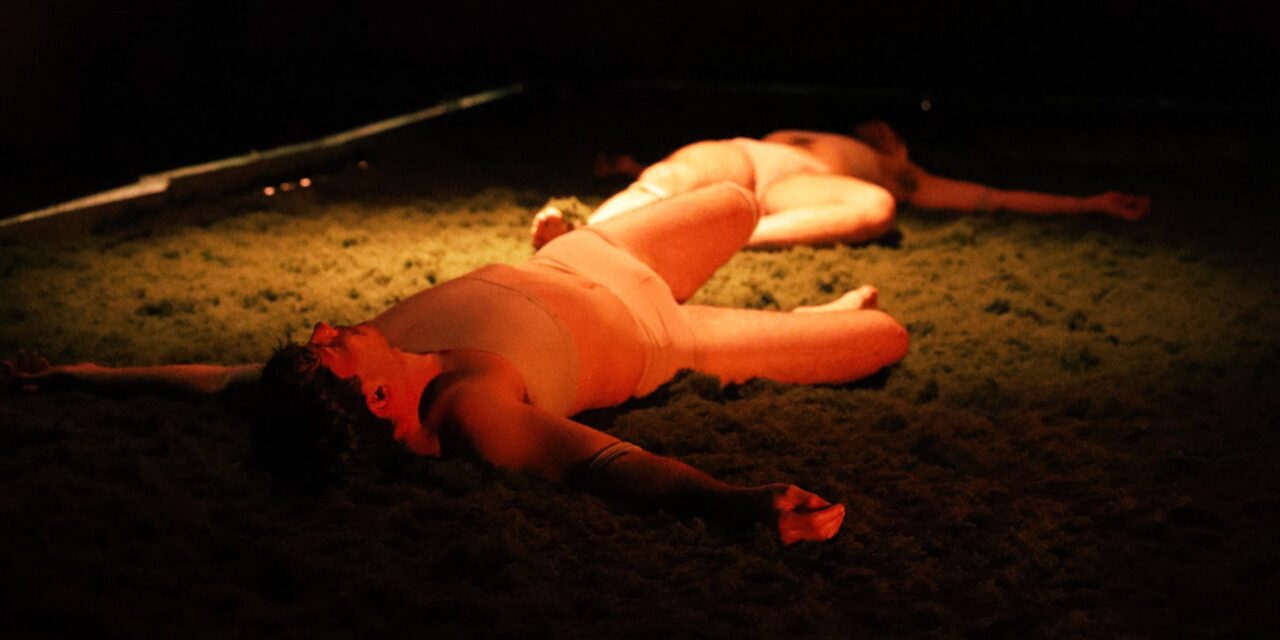

Dance at the Odyssey – Bethany Violett and Rachel Stanfield in Neaz Kohani’s SISTER IS MY SISTER – Photo by Winnie Mu.

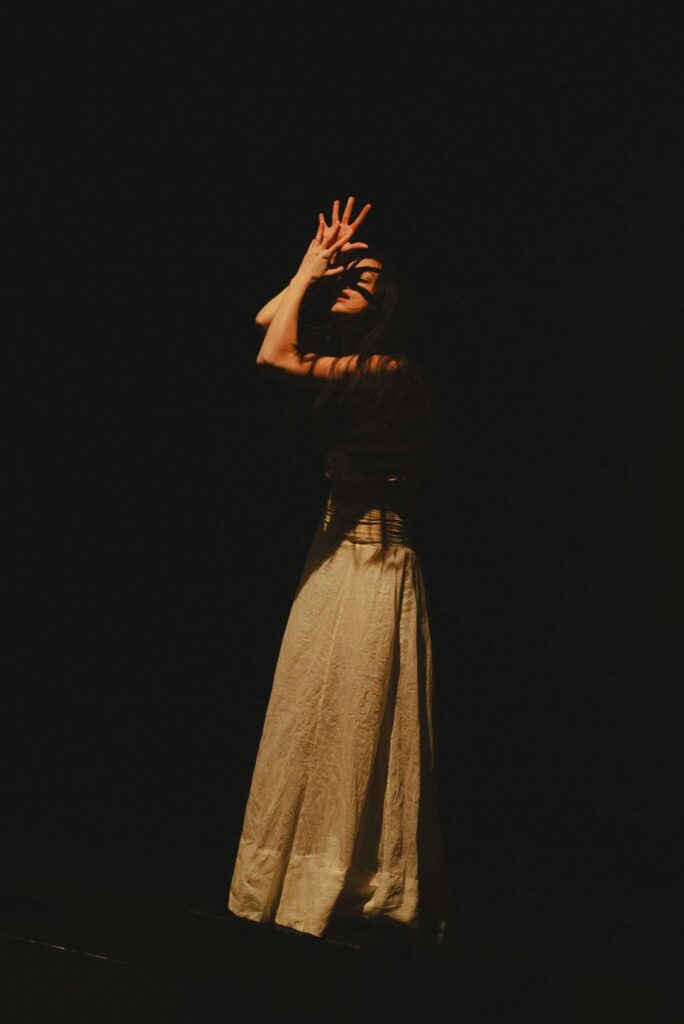

Neaz Kohani’s work was truly exquisite from beginning to end. The dancing by Bethany Violett and Rachel Stanfield was emotional, raw, and powerfully performed, and the live music by Kohani and Jason Hosier was immersive and poignant. Kohani was an invested narrator, and I loved watching how she was connected with the dancers as she sang and spoke. Kohani’s choreography ranged from energetic and sharp to beautifully simple, letting stillness sit with the audience at moments. The hands were often especially detailed, and some of the shapes reminded me of mudras (hand gestures) from classical Indian dance. Throughout the work, gestures and motifs came back and felt familiar. This choice seemed to intentionally comment on the cycle of female wisdom keepers being persecuted. While some of the lyrics referenced “burn[ing] that witch,” the overall feel of the piece wasn’t set in a particular time period and told a universal tale.

Violett and Stanfield’s dancing was fantastic, and they were committed to the story and to each other. They were dressed in white Victorian-esque undergarments with their long hair flowing. The costumes alluded to a style of clothing that would be restricting, but the lack of the structured outer garments and the loose hair spoke to their role as women who were not complying with society’s structures and demands.

The piece started and ended with the dancers moving together, and I was impressed with the structure of the piece that Kohani created with a small cast of two. After an opening section, Violett danced alone, and shortly after Stanfield rejoined, she seemed to die. Stanfield emotionally tried to help and revive her before they danced together, gathering their strength and eventually finding a peaceful embrace on the floor. The last section felt like a flash forward or epilogue featuring two women embracing their sisterhood and sharing their pain. The characters seemed to be fluid – Violett and Stanfield represented different female storytellers at different times. The accompanying songs and spoken word often included repeating lines, many of which stuck with me: “Sister, I see that you have fallen,” “Can I meet you there inside your pain?” and the closing thought “More love is the way.”

The choreography often featured pulsing and writhing actions, angular shapes, and powerful accented hits. At times, the movement was percussive and the sharp punctuation seemed to match the way a speaking voice sounds, while at other times, the dancers were more fluid like the instrumentation or Kohani’s singing voice. Kohani’s intentional structure was highlighted when certain choices would reappear with new meaning. In a solo section, Violett paced in a quick circle, and later, I noticed her repeat this action around Stanfield. In the intimate space, use of sound as part of the choreography was able to be successful even when the sound was a gentle pitter patter of a dramatized bourrée, breath sounds, or the swishing of fabric.

The lighting, done by festival lighting designer Katelan Braymer, was simple and effective in the small space. Subtle shifts in lights made the space feel finite in one moment and then like an endless void, by obscuring or lighting the back wall. The small space featured an entrance in the back left corner of the stage and the audience seating was in an L-shape. Kohani often highlighted the diagonal from this entrance to the center of the audience in her choreography.

I was incredibly impressed by the whole work, and Kohani’s immense skill as a choreographer, poet, singer, musician, and storyteller. As soon as it ended, I could have watched it all again.

Owen Scarlett’s “GASP” welcomed us back after intermission with an intriguing set up. The small stage space was mostly taken up by a large rectangular frame on the floor, which was filled with mossy grass. The wooden frame also had enclosed lighting that created a glowing border, and these lights changed at times in the piece. After the clear story of the first offering, “GASP” was more abstract, and at times confusing.

In darkness, the journey began with a recorded voiceover guiding the audience through a moment of mindfulness. The lights rose and the opening image was memorable as the two dancers, Zach Greene and Derek Tabada, lay in the lush mossy setting while subtle ambient sounds played. The piece seemed to have three somewhat distinct sections with shifts in overall mood and soundscore. Their costumes were nude shorts and bra-like tops, and I liked the gender neutrality of the choice of the top. In the first section, the two dancers slowly awoke and curiously began to move in the unique setting with languid undulating actions. I especially enjoyed when they interacted with the texture of the mossy substance on the floor. It felt otherworldly, as if they were other creatures who woke up in the bodies of humans on a beautiful mysterious planet and were getting used to their new bodies and setting.

The music became more electronic and the dancers began to interact, eventually shifting into a section that became combative at times. The dancers had seemed so peaceful to start, and they had done the same movements in canon, so the shift to a conflict was unclear. Scarlett created complex interwoven partnerwork sequences, and I liked how the section slowly built by repeating the phrase and adding a bit more each time. However I wanted a bit more from the dancers. It felt like there wasn’t quite enough trust in each other or like they couldn’t move fully without abandon in the confined space. After the softer first section, the set felt less necessary and like more of an obstruction.

The transition into the third section featured an extended pause with the dancers laying on the floor while the sounds of breaths were played. I noticed that one dancer seemed to try to intentionally breathe in an exaggerated way to accompany the sounds, while the other was still. I think I would have rather heard their real, heavy breathing after the exertion of their dancing, and the fact that the produced sound was female in contrast to the male-presenting dancers added a layer of inauthenticity.

In the third section, set to techno dance music, more of these differences between the dancers appeared. The choreography was simpler and often repeating to match the beat of the music, so differences like the head position and gaze or the curve of the spine were easy to notice. The differences needed to be more extreme to be effective as an intentional choice if that was the goal. I enjoyed the choreography in this section which was at times humorous and unexpected, and that matched the music well with the use of repetition, angular arms, and continuous pulsing rhythm. As the piece ended and the dancers collapsed on top of each other, I once again wanted to see their breath more and feel them release, but it felt like they weren’t fully relaxed into each other in this final pose.

Scarlett had interesting ideas, his dancers were strong and dynamic, and I enjoyed the choreography, but wanted the structure of the piece to be more or less abstract, and for me, it was too in the middle and did not quite succeed at either a clear narrative or a plotless journey. I thought the set piece was interesting but underused and maybe restricting. If the piece is further developed with the set, I’d be curious to see what it would look like if the dancers started to explore the space outside the frame and what that might mean.

Kudos to the Odyssey and Festival Curator Barbara Müller-Wittmann on the compelling selections for this evening, one of many line ups, of this year’s Dance at the Odyssey Festival.

Dance at the Odyssey continues through February 15, 2026. To see the full schedule and to purchase tickets, please visit the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble website.

Written by Rachel Turner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Feature photo: Dance at the Odyssey – Zach Greene and Derek Tabada in Owen Scarlett’s GASP – Photo by Dillon Howl.