Junyla Silmon lies on an elevated platform covered in turf, stretching her leg until she rolls off. She elegantly catches herself, turning the moment into a dance. She contorts her body, leaning against objects on stage. The moment is relatively quiet, but a bold statement for choreographer Ogemdi Ude.

One of the poignant moments in her research for “MAJOR,” a dance theater project exploring majorette dance, was a performance clip of the Alabama State University Stingettes showing one of the dancers fall and quickly recover, continuing the routine. Ude’s latest show, which was presented by USC Visions and Voices, recently stopped at USC’s Bovard Auditorium for its LA premiere, captures the persistence it takes to be a majorette. As she deconstructs and reconstructs the art form native to the American South within Historically Black Colleges and Universities from the 1960s to the present, Ude pays homage to its cultural importance in Black girlhood. The show is about passing the baton to the next generation of Black women seeking a reason to persist. Throughout the performance, Ude posits that the dance isn’t for you — the audience — to enjoy, but rather a proclamation of Black femme existence and excellence.

Ude created the work in collaboration with archivist Myssi Robinson, ensuring that they honored the history of majorette dance throughout the process. In a social video with On the Boards, Ude shared that the physical side of the work centered on connecting the past with the present, attempting to bridge her memory of majorette dance (“a body that is in your history”) with the abilities of her current dancer body. This intention comes through from the start of the work. Following Silmon’s introductory solo, where she slowly re-learns how to move, the ensemble steps in front of a pyramid of mics and verbally announces the steps of a routine, including the movement of a limb and the pop of the hip. The movement of majorette dance, at this point, is completely deconstructed.

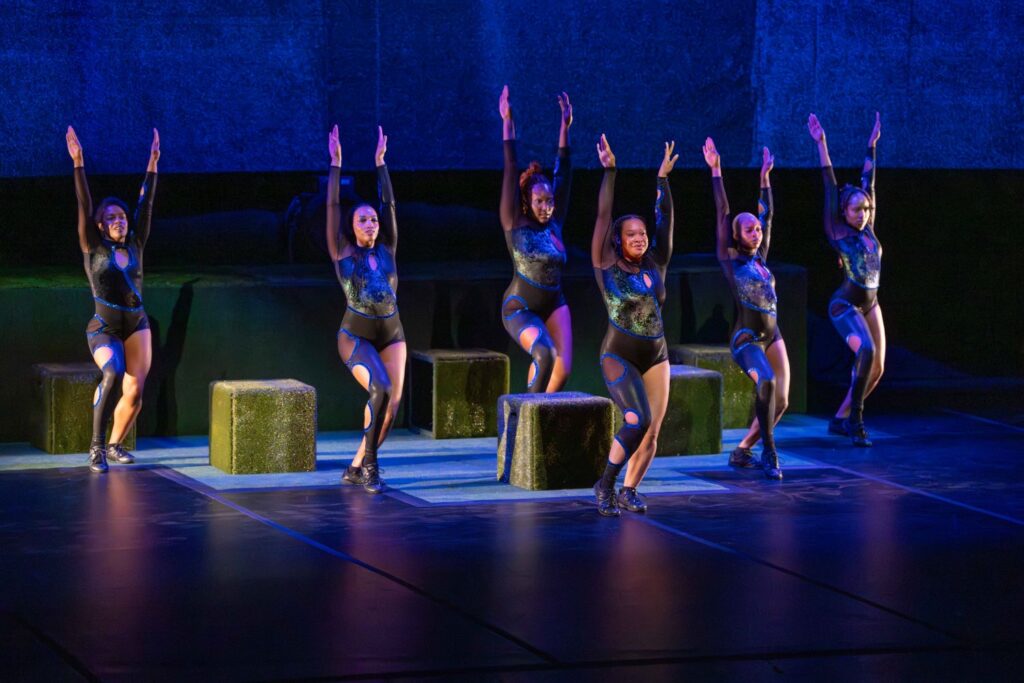

The choreography, made in collaboration with the performers (Camille Phelps, Jailyn Phillips-Wiley, Silmon, Kayla Farrish, Song Aziza Tucker, original collaborator Chanel Stone, and dance captain Selah Hampton), meshes contemporary dance with the blend of jazz and hip hop present in majorette dance. The choreography is smart, shifting from the undulation of the hips to a balletic weight shift. The sophistication of movement is best seen in the twerking section of “MAJOR.” The majorette team brings life to Lambkin’s musical composition, heightening the energy with each eight-count. Phillips-Wiley steps out of formation, initiating the movement’s evolution with a sensual, heartfelt solo representing the very meshing of past and present that Ude commented on. Following the disruption, they all begin to twerk. Here, they play with connection, levels and tempo. First in unison, they let the movement take control. It becomes an experiment where they let fate tell them how they reconnect and disconnect.

Song Aziza Tucker is a standout performer in this entrancing section. As the bounce becomes more erratic, she lets it dictate her direction and relationship to the space. She steps down to the audience. She stands in front of the light. The football field environment created by set and lighting designer Simean “Sim” Carpenter frames Tucker in a spotlight. Her shadow appears on the walls of Bovard. As she twerks and convulses, her shadows become a conjuring of life with impeccable effort. This harmony of performance and environment unveils the consequences of pushing for more, the exhaustion it brings and the emotional battle for rest in majorette dance. Those who participate in the art form are doing more than moving but confronting the societal expectations of Black femmehood and building their own version of its definition.

“Watch me be grown,” Tucker says. This statement, made with heart and courage, is the crux of the work. Through Tucker’s passion, both in voice and movement, the value of majorette dance in one’s upbringing is emphasized. This work is about the community and the freedom it brings to be proudly Black and femme.

“This is a rupture,” she says.

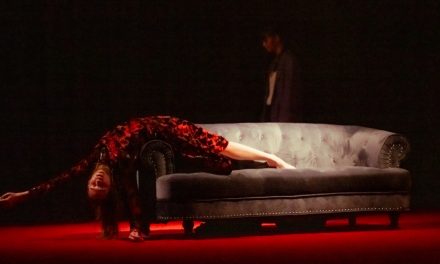

The unexpected twist of romance disrupts the pacing of the work. As two performers alter their sisterhood into romance, a new stem of majorette dancing comes to fruition. The other performers leave, and the lights become moodier. The deconstruction and reconstruction of dance moves return as they show each other various steps. The section isn’t just about majorette dance, but how people learn to be queer and discover the language society forces us to suppress. The execution, while loose and slightly off course, makes space for a necessary reflection on the breadth of femininity. It is just as much part of the majorette narrative.

In the grand finale, Ude welcomes four performers of The Cardinal Divas of USC to dance alongside members of The Spirit of Troy marching band. Throughout the tour, Ude aims to highlight local majorette teams and marching bands within the show. Here, the statement is particularly powerful. Established in 2022, the Cardinal Divas brought the culture of HBCU to a predominantly white institution, claiming space at some of the university’s biggest games. It echoes Tucker’s “watch me,” bringing together generations of majorette dance. As they each perform a short solo, they make people watch and bask in the communal magic of majorettes. Through movement, each majorette dancer shares what the art form means for them. Ude fulfills her promise to uplift the next generation with this piece, concluding with a final statement: “I can be grown too.”

As I step outside Bovard Auditorium, the message echoes. A student trots away from the venue with energy beaming out of her. She brings her phone to her ear and says, “I want to do majoring again.”

To learn more about Ogemdi Ude, please visit her website.

For more information about USC Visions & Voices, please visit their website.

Written by Steven Vargas for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: “MAJOR” choreographed by Ogemdi Ude – Photo by Henry Kofman.