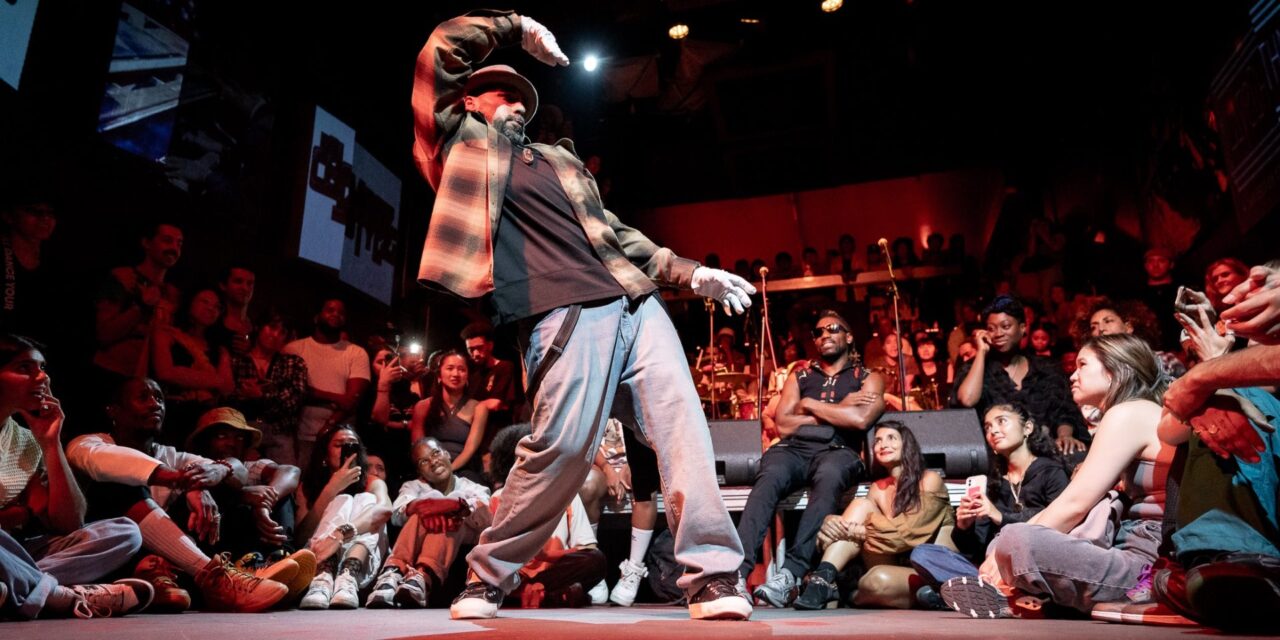

If you did not read my January 29 review of “Versa-Style and Friends: Celebrating the Street Dance Community,” let me introduce you to Boogie Frantick.

“Boogie Frantick’s piece, ‘Chicano Power,’ illustrated why he’s a master. The local legend entered the stage in his signature slo-mo strut and with Carla Morrison’s hypnotic ‘Azúcar Morena’ playing, he combined all his styles—including animation, ticking and waving—into a riveting one-man statement.”

I met Frantick in 2013; his career was back on track after a brief hiatus. His resume lists TV, stage and screen appearances at the Academy Awards with the Legion of Extraordinary Dancers for the Hurt Locker score; with Snoop Dogg, Talib Kweli, Hit-Boy and Egyptian Lover; and in the film Step Up 3D. He has collaborated with brands such as AT&T, Frito Lay, Microsoft, Red Bull and WSS.

“I remember starting my dance journey as far back as 2 years old,” Frantick said. “I know that’s pretty hard to believe, but I remember confirming this with a couple of my cousins, and they were even surprised that I had a memory of dancing in a movie theater back when the red velvet curtains used to hide the actual screen. It was like 1984. I just remember being able to do certain movements, always following my older brothers and sisters and my cousins because at the time they were old enough, they were almost teenagers at the time, to be dancing. The hype was real, especially back in the ’80s.

Popping and breaking were the popular street dance styles. It was common to see dancers carrying a cardboard around.

“I remember they used to make special cardboards back then where you could actually fold it up and carry it, and they had a handle,” he said. “People were carrying boomboxes back then. The memories of those times are why I continued to dance as I grew older. By 9 years old, I wanted to dive in and master popping.”

Frantick was good at mime and characterizations, as he tells it. His friends would often ask him to “do the thing with the typewriter” or “do the wall.”

“I just had particular ways of entertaining my friends, so that to me was my journey of self-study and self-mastery,” he said.

Frantick’s earliest influences were black and white movies from back in the day that he would watch if you were a kid like him who stayed up late and was home alone most of the time. Cartoons also helped his creativity with movement. Even movies like Dick Tracy.

Frantick was not inspired by the commercial music of the day; rather, he liked movie scores and his uncle’s band.

“There were times when my mom would sneak me into a bar because she couldn’t afford a babysitter,” he shared. “So that was interesting for me to see older people act a fool. I didn’t really dance so much at those kinds of parties, but it made me appreciate music for what it is and the power of the instrument.”

One of Frantick’s cousins, Eddie Avila, was a drummer who made a lasting impression on him.

“I remember watching him and thinking, how is he playing with his eyes closed? But when I started to do the same, I noticed that my body started to move way more. Then I started to find the pattern of where he was playing, and I could actually catch my footwork. I started matching how he was playing, like the symbols versus the snare drum, the snare drum versus the heavier drum, the kick drum versus the high hat. I really wanted to tap into that and illustrate the sound as deep as I possibly could.”

The foundation of Frantick’s movement is ticking. He drilled into ticking and dime stops, waving and glides, then popping and breaking.

When Frantick was handed a VHS tape of the 1984 dance drama, Beat Street, he was instantly hooked on popping.

“I was just blown away by the essence of hip-hop and how it was represented in that movie,” he said. “It just naturally made me connect even further. Hip-hop started to become more of the purpose behind my movement.”

Just as Frantick was finding his identity as a dancer, he lost both of his brothers. In 1995, his one brother was murdered due to gang violence in East L.A., and his other brother was incarcerated for about 6 years.

“I just remember my mom walking into the room and telling me, and for me, I didn’t know where else to go,” he said. “It was really difficult for me to find a father figure at that time. I wasn’t really talking with my dad, so it was very difficult for me. I felt like, OK, you know what? I’m gonna dance. I’m gonna practice and keep this going. This is pretty much all I have.”

“It was really because of my childhood memories that made me understand how important this was and keeping the happiness and the family-oriented memories alive, while keeping my movement alive,” he continued. “I even danced in front of my brother’s casket, so it just solidified, this is who I need to be and what I want to be.”

By 1996, Frantick shared that the world had opened up for him. He met other breakers and poppers in middle school.

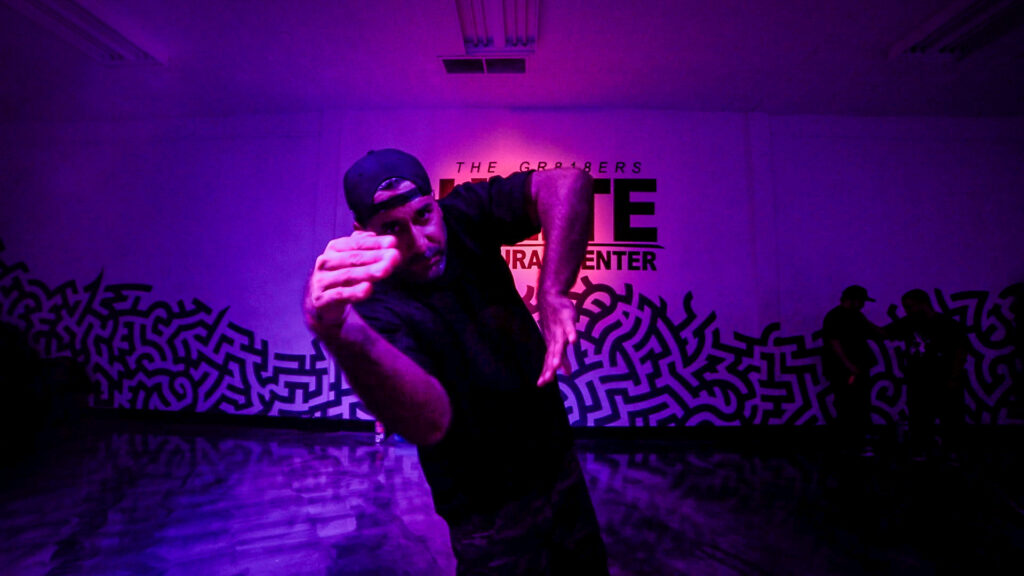

“I had no idea that I wasn’t the only one, like wow, there’s an actual world out here of people doing this as well,” he said. “I just felt like I was walking in the right footsteps.”From his days in middle school, Frantick’s mentor Hazze had dreams of starting a hip-hop culture dream center. An offshoot of the idea, The GR818ERS, was eventually launched in 2010 by youth as a collective of artists, athletes and activists dedicated to improving social conditions in their community. The “818” area code represents their pride in the San Fernando Valley as a global cultural force.

“I have always represented for the 818,” Frantick said. “I was raised in the entire San Fernando Valley. I’ve lived in 17 cities in the San Fernando Valley alone.”

The GR818ERS host workshops, enrichment programs, events and an annual Flava of the Year street dance competition.

These days Frantick is focused on giving back. He recently launched an online intensive, a four-lesson course composed of foundation, animation, ticking and waving.

“I realized a lot of countries have a large sense of community but don’t have the understanding of culture and what they’re trying to dive into,” he said. “My thing is, it’s always a connection. It’s always been spiritual for me. I’ve cried during performances. It’s been therapy for me. It’s also difficult for me, trying to get better and training for competition. It’s been athletic for me.”

“I’ve made people cry, made people happy,” he continued. “I’ve made people see they can do more for themselves and that to me is more deeply rooted than anything. For me to have that impact. I was just trying to get away from a negative lifestyle, and I’ve always tried to see the light in any situation, and dance has been able to help me do that. If I could do that for anybody else and train them to see the benefits of sticking to something and being very disciplined, why not?”

To learn more about Boogie Frantic, please visit his website.

Twitter/IG: @boogiefrantick

YouTube: theboogiefrantick

Written by Jessica Koslow for LA Dance Chronicle.

Feature image: Boogie Frantick – Photo courtesy of the artist.