A Martha Graham work is easily identifiable by the feeling it can conjure. Whether it be a sharp contraction of the core, a cupped hand or a complex relationship with the torso, Graham captures the feeling of breathlessness and the fight for strength within it. To ring in the final season of Martha Graham Dance Company’s three-year centennial celebration, the company bridged a historic 1947 work with a posthumous world premiere to highlight the timelessness of her technique and aesthetic.

The presentation at The Soraya Center for the Performing Arts on October 4, 2025, included the premiere of Hope Boykin’s “En Masse” with music by Christopher Rountree—inspired by the growing collaboration between Graham and composer Leonard Bernstein—Graham’s “Night Journey” with music by William Schuman, and Jamar Roberts’s “We the People” with music by Rhiannon Giddens.

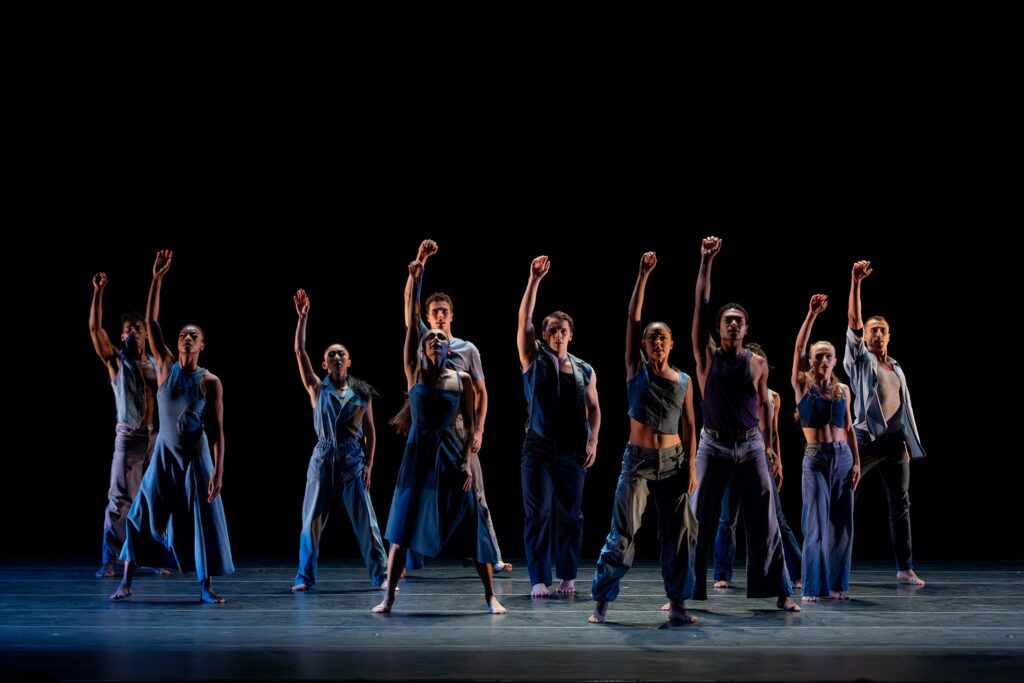

The Martha Graham Dance Company’s Leslie Andrea Williams performs in En Masse, choreographed by Hope Boykin, a The Soraya co-commission – Photo by Luque Photography.

“En Masse,” the centerpiece of the night, spawned from a recently discovered Bernstein piece titled “Vivace.” Graham and Bernstein had been in the same circles throughout most of their career, but they didn’t start discussing a possible collaboration until 1988, when Graham wrote to Bernstein asking to work together on a reimagining of her 1938 ballet “American Document.” Throughout 1988 and 1989, they mailed letters to each other. They met several times to share ideas about a work consisting of American texts, including the Declaration of Independence and (with Bernstein’s suggestion) Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. The collaboration never came to fruition due to Bernstein’s demanding conducting schedule. With the discovered score sketches believed to be written for Graham, Wild Up’s Rountree composed a work inspired by Bernstein’s piece alongside new musical arrangements of excerpts from Bernstein’s “Mass.” Meanwhile, Boykin’s choreography took inspiration from Graham’s movement language and technique. Together, Boykin and Rountree created the first posthumous partnership between Graham and Bernstein.

The Martha Graham Dance Company in En Masse, a Soraya co-commission choreographed by Hope Boykin with music by Leonard Bernstein and Christopher Rountree – Photo by Luque Photography.

The result was a medley of the two 20th-century pioneers that teetered between experimentation and final product. Boykin’s choreography for the variations of “Mass” was a direct homage to Graham’s work. It opens with a line of dancers connected by an elastic band attached to their hands and wrists. As they moved, it stretched, thinning to reveal a tension both amongst themselves in the movement and with one another. The imagery echoes the tension depicted in Graham’s “Lamentation,” where she is covered in an elastic garment that changes shape as she moves and contracts her body.

As the variations continue, the elastic bands are discarded, and the movement alters into a jazz-influenced aesthetic. Similarly, the arrangement changes. Emphasis is placed on the horns and percussion, slowly growing into a frenetic percussive climax. The movement falls out of unison as three dancers on stage follow their own track. One may be more balletic, while another may be more theatrical. It’s chaos. It feels like something beyond Graham or Bernstein. We’ve lost track.

The work concludes with “For Martha,” Rountree’s composition inspired by Bernstein’s “Vivace.” We make our way back to the original vision. A single dancer moves in a rectangular spotlight portrayed on the ground. They shape the air with their arms and move as if they are floating in the ocean of light. Suddenly, the ensemble of dancers rushes in, running in a circle and through the spotlight. We lose the soloist until the crowd leaves. In the frenzy, the soloist remains. Boykin’s choreography features profound formations that pay homage to Graham’s legacy and reflect Boykin’s own taste. The movement language is the perfect balance between Graham’s grounded technique and Boykin’s elastic turns and buoyant balletic movement. Even in the most technical phrases, the texture is so soft that it feels as if the performers are strolling through the movement.

Ann Souder as Jocasta in Martha Graham’s 1947 piece Night Journey. Behind Souder is Ethan Palma as Tiresias the Seer, and on the left are the Daughters of the night – Photo by Luque Photography.

The work is perfectly paired with Graham’s “Night Journey,” which started the night. The work is a classical reinvention of the tragedy of Oedipus (Lloyd Knight), shown through the perspective of his mother and wife Jocasta (Anne Souder). The Daughters of the Night move in gorgeous costumes designed by Graham that enhance unified phrases. Tiresias, the Seer (Ethan Palma), hones a weightless quality that contrasts Oedipus’s weighty, grounded steps. Their performances perfectly capture the tug-and-pull they have on the leading woman. Souder, challenged with the task of depicting the emotional journey to suicide, crafts a strong emotional arc with intentional details inside the choreography. Schuman’s music helps highlight her choices. For example, as she digs deeper into the psyche, the woodwinds pierce through the strings. She is pulled out of a trance and grounds herself for a sultry section with Oedipus.

Jocasta begins the piece holding a rope around her neck. Here, Souder trembles with a staccato shake of the arms. It’s big and nearly performative, reflecting Jocasta’s initial thoughts of taking her life. It is simply an idea that hasn’t been fully developed. By the end of the piece, she holds the rope again. This time, there is only a soft tremor in her arms. It’s firmer and more assured. Sounder’s performance is astoundingly heart-wrenching and surprisingly romantic, reflecting the complex thoughts that drive her toward her death.

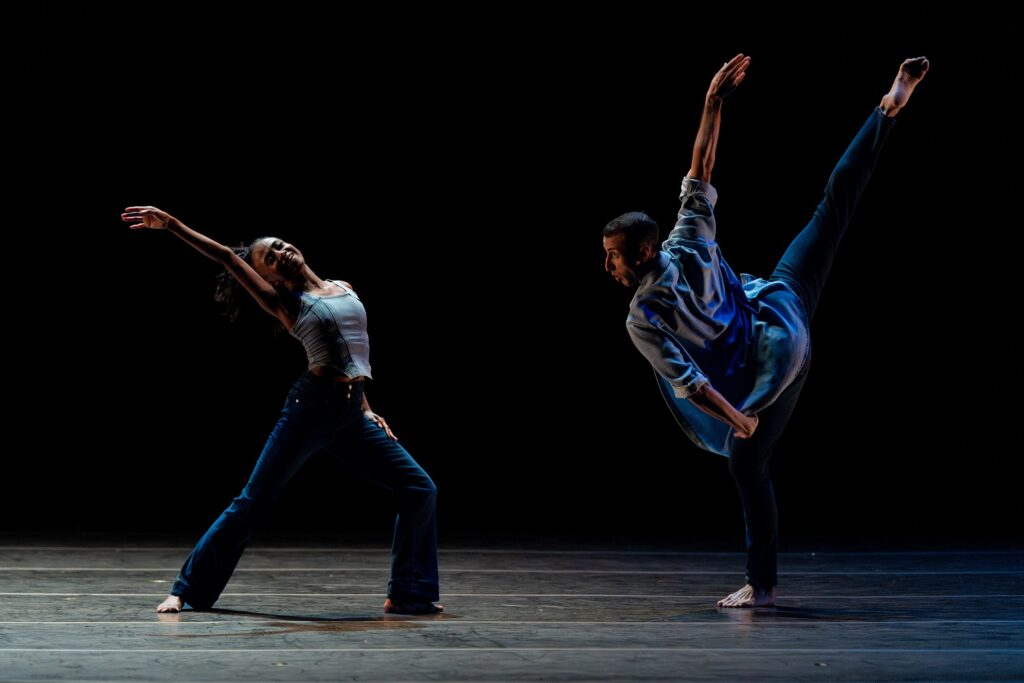

Jamar Roberts’ “We the People” is the most unexpected and profound work of the night. The piece, with a new score by Rhiannon Giddens arranged by Gabe Witcher, reflects on American history with the sounds of folk music. The work created in 2024 for the centennial celebration is described as a lament and protest, depicting the importance of collective change. Sections of silence separate the piece. Leslie Andrea Williams begins in silence with a dynamic solo that reflects Roberts’s choreographic approach to tempo and textures. The movement is like a yo-yo, easing from slow-motion to quick bursts. Her arm swings quickly before slowly shifting to a halt. It begins again.

Roberts has a way of letting each dancer’s talent shine, allowing bits of their self-expression and authentic movement to peek through the choreography. In a duet between Richard Villaverde and Meagan King, that same yo-yo texture returns, but this time it feels different. Villaverde’s findings allow experimentation with tempo to influence the tension in his body. He moves slowly in moments of calmness and tenses as it feels dangerous. King shifts the weight in her body with precision, proving she is a force to be reckoned with.

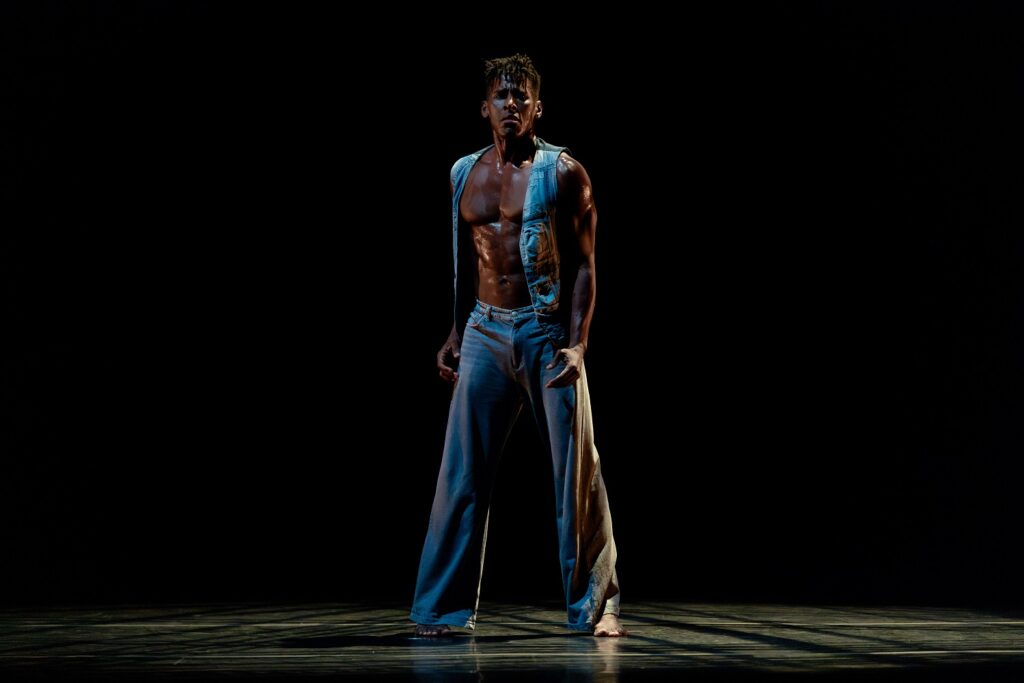

The final solo by Knight contorts the American iconography established throughout the work. The imagery of winding a lasso slows until Knight holds up a fist, a symbol of resistance and protest. As established in Roberts’s choreographic language, there is rarely a moment of stillness. This fist keeps going in slow motion, moving back as if ready to swing forward and fight. By the end, the imagery of the fist changes again when Knight lands on the ground with his arms behind his back, referencing the imagery of police brutality.

Throughout the solos and vignettes of “We the People,” we get a glimpse into the differing experiences of life—how one’s identity can dictate their navigation of the world. In the final group section, all these stories and perspectives come together. The movement language sings a different tune, one of fatigue and fury. It feels more alive. Roberts’s work tells a story of communal resistance and how the real work starts when we come together for a common cause. No matter our background, injustice against one person impacts us all. Roberts captures this beautifully when the fist returns. The ensemble moves in unison until they all recoil from an invisible punch. They experience the recoil differently, whether it is a head tipped backwards or the fling of an arm. Once they’ve recovered, there’s a strong moment of stillness, chests high and chin up. The constant motion and toying with tempo make these final moments so much heavier to witness.

The program marking the start of the centennial celebration’s final year upheld astute curation, weaving Graham’s themes of collaboration and storytelling across years of artistic work. As a whole, it captured the essence of Graham—contraction and cupped hands included—within its most subtle textures and bold choices.

To learn more about the Martha Graham Dance Company, please visit their website.

To learn more about The Soraya Center for the Performing Arts, please visit their website.

Written by Steven Vargas for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Ann Souder as Jocasta in Martha Graham’s 1947 piece “Night Journey”. Behind Souder is Ethan Palma as Tiresias the Seer, and on the left are the Daughters of the night. Photo by Luque Photography.